A leader’s primary job is to make good decisions. These decisions require judgement. As leaders we don’t always see the situation clearly when under stress. Stress can trigger overly emotional and irrational internal narratives (e.g. “I have to be 100% right before I speak” OR, “this person thinks I am too old to know about change”) that drive our reactive and self-protective behaviour to circumstances, leading to impulsive and often bad choices. These bad choices are driven by mind-driven fears and narratives rather than external evidence.

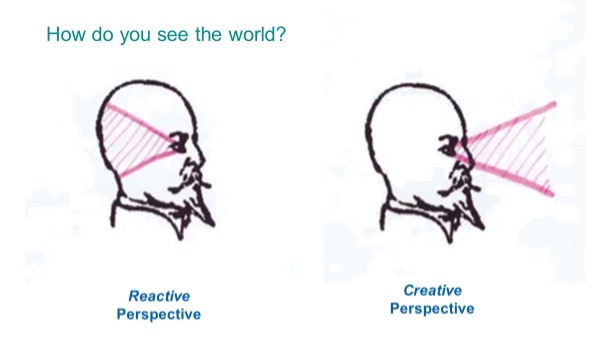

As a leader are your decisions grounded in the current reality, resulting in a creative response, or in the historical fears and biases of your mind, resulting in a reactive protective response?

The world we see is mind-created, not a pure reflection of reality. Therefore, we are often living in a controlled hallucination. Fundamental to human development and maturity is to awaken from this world we make up, the one we have imprisoned ourselves in. To awaken is to witness our hallucination, and own it, so it doesn’t own us. We can become adept at observing the version of the world we have constructed and re-aligning that version (hallucination) with one that is more closely happening in the here and now. If not a pure reflection of reality, a perception that is more compatible and aligned with current circumstances, and not historical fears and insecurities.

Evolutionary forces have programed us to survive and pass on our genes. Evolution doesn’t care about what is real; only what helps us survive. Our hunter gatherer ancestors lived in a dangerous time and learned a healthy fear reaction and set of fight or fight behaviours to what rustled in the trees. Back then, being fearful made good sense. A fearful attitude drove much of their perceptions and actions, keeping us alive.

Hundreds of generations later, like our ancestors, we as children, developed strategies to remain safe in environments where we were relatively powerless around those who held the power. Our parents, teachers, older, stronger kids. Those strategies were “useful” for self-protection and survival. Over time those strategies became unconscious habits triggering negative emotions (fear) and reactive behaviours (freeze, fix, fight, or flight) when we perceived we were under threat. A threat now being a fear of loss of value to our group, rather than a real physical threat from that bear in the bushes.

In my case, my automatic reaction to an angry or negligent mom was to entertain her, to show her how funny and smart I could be. I could make her stop screaming, stop ignoring me, and rather laugh and show her approval and affection. Long after leaving my childhood home, this reactive tendency became a deeply embedded habit that played out in impulsive behaviours when I was triggered to feel unsafe or insecure in social and work situations. I would take up too much space in client meetings or offsites, trying too hard for approval. When tension grew, I would jump in and save the day. Today, I am more likely to sit back, quietly, and allow the tension and group discomfort, patiently waiting to see who and what emerges from it. In my personal life, at a dinner party, if I wasn’t getting enough attention, if I wasn’t feeling valued enough, I would dominate the conversation, double downing to impress.

Long after my mother was gone, this habit to show off and attract undue attention to myself, when feeling under-appreciated, was no longer useful to keep me safe, and rather would often serve to alienate and isolate me further from the other important person or group I was part of. Through practice and hard work, I now note my impulse to take over, show off, and impress. I can now internally smile at this tendency and let it dissolve in me and see what emerges from a quieter mind, ego and body.

As adults, when we see life as a scary place (a mind-created reality) and our primary concern is safety, we tend to play not to lose, rather than play to win. Unexpected events or change can seem threatening to our sense of stability and overall identity, thereby eliciting a negative emotion (e.g., unwarranted fear) that triggers a reactive behaviour which may have been useful as a child, but no longer. Our mind (reactive, unconscious habits) constructs a “reality” that seems more threatening, rather than just new or different. Fear drives the controlled hallucination.

When we see our reactive mind for what it is, a set of somewhat out-dated assumptions, beliefs and habits developed for childhood survival we can wake up from its hold on us. Rather than us being the unconscious, impulsive reactor, we become the witness to our reactive tendencies before they play out. The witness part of ourselves then decides, is this a situation I must defend against, or should I embrace this change and figure out how to update and re-calibrate my attitudes and subsequent behaviours in alignment with the novel situation? We can experience the new circumstances of current reality as not threatening, and not something to defend against. We can let go of our knee-jerk self-protective behaviour and instead respond with curiosity and creativity to the newness.

So, how does this relate to leadership?

A leader’s primary job is to make decisions. Good decisions come from making the right choices. The right choice is informed by the most accurate version of reality that the leader can see. Effective leadership requires a leader to be aware and critical of her historical mind-driven reactive tendencies, unconscious habits, assumptions, and hidden beliefs that can distort their view of what is happening today. Pause, to re-calibrate her view to one that is more reality informed than mind informed, and then respond with mindful presence and inherent creativity to the situation at hand.